What exactly happened in Paris in that spring of 1874, and what sense should we make today of an exhibition that has become legendary? “Paris 1874. The Impressionist Moment” seeks to trace the advent of an artistic movement that emerged in a rapidly changing world.

“Paris 1874” reviews the circumstances that led these 31 artists (only seven of whom are well-known across the world today) to join forces and exhibit their works together. The period in question had a post-war climate, following two conflicts: the Franco-German War of 1870, and then a violent civil war. In this context of crisis, artists began to rethink their art and explore new directions. A little “clan of rebels” painted scenes of modern life, and landscapes sketched in the open air, in pale hues and with the lightest of touches. As one observer noted, “What they seem above all to be aiming at is an impression”.

In “Paris 1874”, a selection of works that featured in the 1874 impressionist exhibition is put into perspective with paintings and sculptures displayed at the official Salon the same year. This unprecedented confrontation will help recreate the visual shock caused by the works exhibited by the impressionists, as well as nuance it by unexpected parallels and overlaps between the first impressionist exhibition and the Salon.

The exhibition at Musée d’Orsay evidences the contradictions and infinite variety of contemporary creation in that spring of 1874, while highlighting the radical modernity of those young artists. “Good luck!” one critic encouraged them, “Innovations always lead to something.”

This exhibition is organized by the Musée d’Orsay, the Musée de l’Orangerie and the National Gallery of Art, Washington, where it will be presented from September 8, 2024 to January 20, 2025.

List of works

178 prepared works, 34 participating institutions, 13 represented regions

- AJACCIO

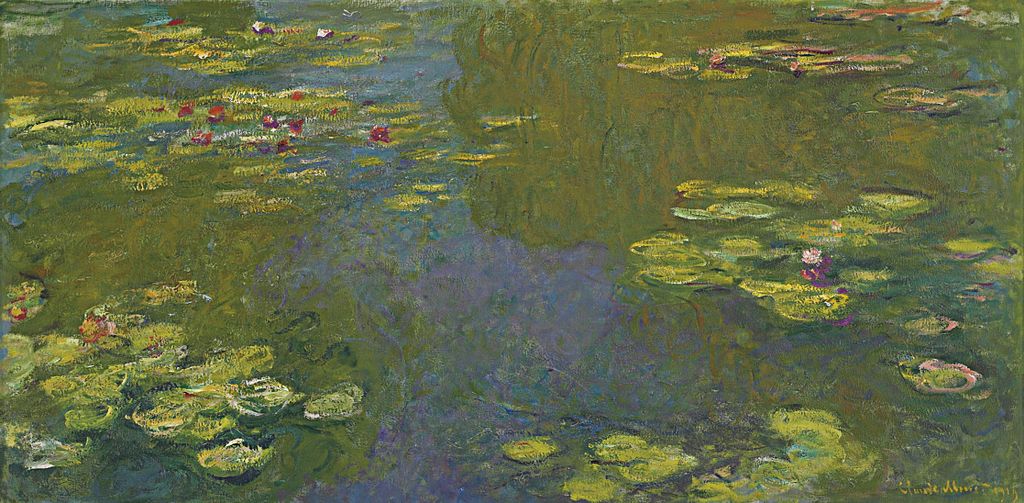

- Claude Monet, Le Bassin aux nymphéas, harmonie rose, 1900

- Claude Monet, Le Bassin aux nymphéas, harmonie rose, 1900

- ALBI

- Auguste Renoir, Charles Le Cœur, vers 1872-1873

- Berthe Morisot, Sur un banc au bois de Boulogne, 1894

- Auguste Renoir, La Liseuse, 1876

- Auguste Renoir, Charles Le Cœur, vers 1872-1873

- AMIENS

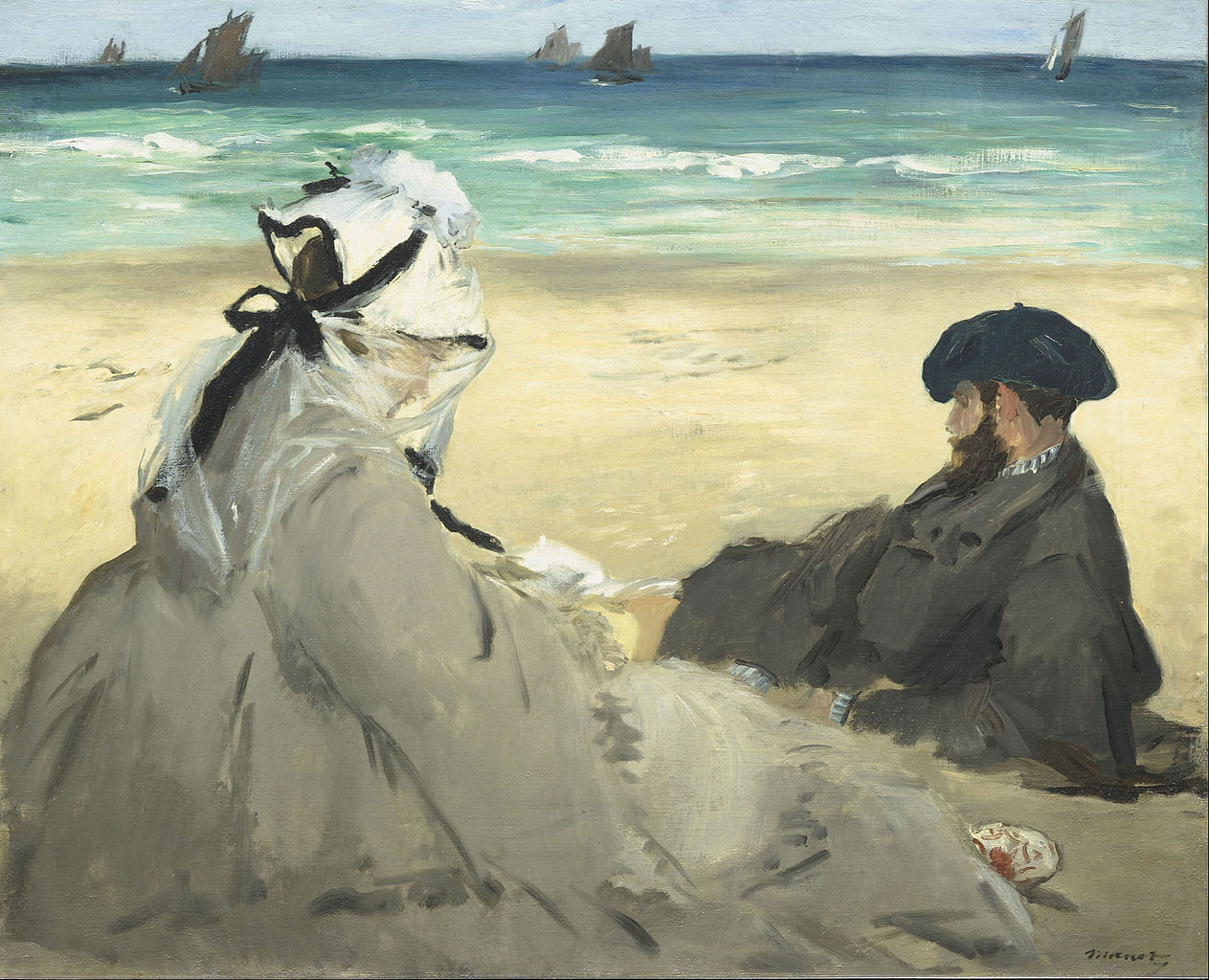

- Édouard Manet, Sur la plage, 1873

- Édouard Manet, Sur la plage, 1873

- ARLES

- Vincent van Gogh, La Nuit étoilée, 1888

- Vincent van Gogh, La Nuit étoilée, 1888

- BAYEUX

Georges Seurat, Port-en-Bessin, avant port, marée haute, 1888

- BESANÇON

- Claude Monet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe

- Claude Monet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe

- BORDEAUX

- Édouard Manet, Le Balcon, 1869

- Édouard Manet, Le Balcon, 1869

- CAEN

- Joseph Hornecker, Les Magasins Réunis à Épinal, projet de décor des façades, 1908

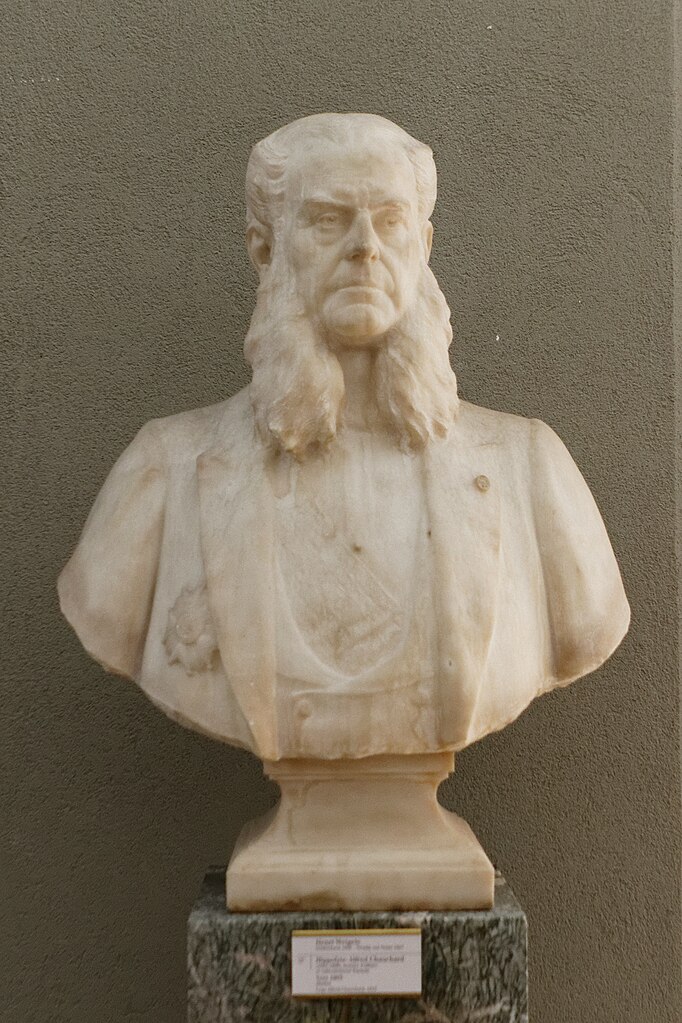

- Henri Weigele, Alfred Chauchard assis, 1903, sculpture

- Maximilien Luce, Scène d’intérieur, lithographie

- Constant Puyo, Manhattan Photogravure Company, Montmartre, 1906

- Alfred Stieglitz, Manhattan Photogravure Company, A Snapshot :Paris (1911), 1913

- L. L., Paris, boulevard des Italiens, 1890 (tirage moderne)

- Henri Lemoine, Bouquinistes sur le quai Conti, 1900

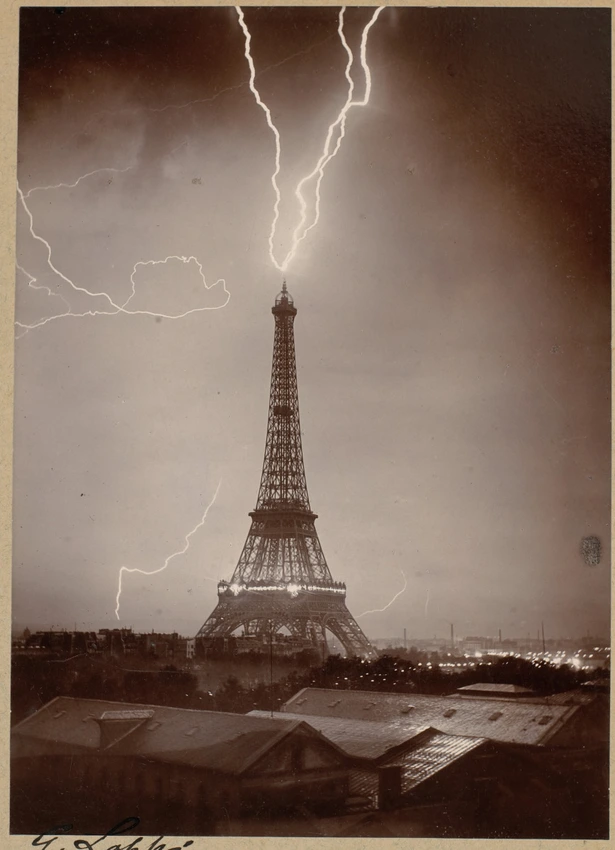

- Gabriel Loppé, Paris : Quai de la Seine, lumière de la Belle Jardinière, 1889

- Anonyme, Paris sous le Second Empire, le boulevard de la Madeleine, 1865

- Anonyme, Paris, le boulevard Magenta, 1865

- Anonyme, Boulevard Saint-Martin, 1865

- Eugène Boudin, Homme derrière un étal à poissons, non daté

- Eugène Boudin, Femme derrière un étal à poissons, non daté

- James Wilson Morrice, Quai des Grands Augustins, 1905

- Louis Valtat, Vue de Paris, 1893

- Pierre Bonnard, Chanteurs ambulants, 1897

- Pierre Bonnard, Place Clichy, 1895

- Eugène Boudin, Marchande assise près de son petit éventaire, non daté

- Marville, Vue du marché du Temple, non daté

- Joseph Hornecker, Les Magasins Réunis à Épinal, projet de décor des façades, 1908

- CHARTRES

- Claude Monet, Le Bassin aux nymphéas, harmonie verte, 1899

- Claude Monet, Le Bassin aux nymphéas, harmonie verte, 1899

- CLERMONT-FERRAND

- John Russell, Le Port de Goulphar sous la neige, 1931

- Albert Lebourg, La Neige à Pont du Château, 1928

- Victor Charreton, La Neige, 1925

- Maximilien Luce, La Neige au quai de Boulogne, 1905

- Claude Monet, La Pie, 1869

- Charles François Daubigny, La Neige, 1873

- Pierre Bonnard, Effet de neige, 1901

- Albert Edelfelt, Journée de décembre, 1893

- DRAGUIGNAN

- Auguste Renoir, Étude. Torse, effet de soleil, vers 1876

- Auguste Renoir, Étude. Torse, effet de soleil, vers 1876

- DOUAI

- Claude Monet, La Rue Montorgueil, à Paris. Fête du 30 juin 1878, 1878

- Claude Monet, La Rue Montorgueil, à Paris. Fête du 30 juin 1878, 1878

- GIVERNY

- Eugène Boudin, Normandes étendant du linge sur une plage, 1865, MNR

- Johan Barthold Jongkind, Le Port d’Anvers, 1855, MNR

- Adolphe Félix Cals, Pêcheur, 1874, MNR

- Auguste Renoir, Petit port, 1919, MNR

- Octave de Champeaux, Clair de lune en mer, 1897

- Eugène Boudin, La Plage de Trouville, 1867

- Eugène Boudin, Voiliers, 1869

- Eugène Boudin, Port de Camaret, 1872

- Eugène Boudin, Port d’Anvers, 1871

- Camille Corot, Trouville, bateaux de pêche échoués dans le chenal, 1875

- Alexandre Marcette, En route. Bateaux sur la mer du Nord, non daté

- Philip Steer, Jeune femme sur la plage, 1888

- Édouard Manet, L’évasion de Rochefort, 1881

- Charles Laval, Femmes au bord de la mer, esquisse, 1889

- Claude Monet, Les Rochers de Belle Ile, la Côte sauvage, 1886

- Eugène Boudin, La Plage de Trouville, 1865

- HONFLEUR

- Claude Monet, La Charrette. Route sous la neige à Honfleur, 1867

- Eugène Boudin, Pommiers à Saint-Siméon, vers 1830-1850

- Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille, 1867

- LE CANNET

- Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, La Femme aux gants, 1890

- Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, Clownesse Cha U Kao, 1895

- LE HAVRE

- Claude Monet, Train dans la campagne, vers 1870, MNR

- Edmond Auguste, Alfred Bacot, Partie supérieure de la façade de la cathédrale de Rouen, vers 1853

- Gustave Le Gray, Le Brick au clair de lune, 1856

- Camille Pissarro, Port de Rouen, Saint‑Sever, 1896

- Claude Monet, La Cathédrale de Rouen. Le Portail vu de face, 1892

- LILLE

- Claude Monet, Les Glaçons, 1880

- Claude Monet, Église de Vétheuil, 1879

- Claude Monet, La Seine à Vétheuil, effet de soleil après la pluie, 1879

- Claude Monet, Vétheuil, soleil couchant, vers 1900

- LIMOGES

- Auguste Renoir, Fernand Halphen enfant, 1880

- MARSEILLE

- Paul Guigou, Lavandière, 1860

- Paul Cézanne, Le Golfe de Marseille vu de L’Estaque, 1879

- MONTAUBAN

- Gustave Caillebotte, Les Soleils, jardin du Petit Gennevilliers, vers 1885

- MONTPELLIER

- Édouard Manet, Le Fifre, 1866

- Édouard Manet, Émile Zola, 1868

- NANTES

- Gustave Caillebotte, Partie de bateau, vers 1877-1878

- NICE

- Berthe Morisot, Les Enfants de Gabriel Thomas, 1894

- Auguste Renoir, Paysage de Cagnes, 1915

- Auguste Renoir, Portrait de Stéphane Mallarmé, 1892

- Auguste Renoir, Portrait de l’artiste, 1879

- Auguste Renoir, Paysage, 1919

- Claude Monet, Les Villas à Bordighera, 1884

- ORLÉANS

- Toulouse-Lautrec, Louis Bouglé, 1898

- Auguste Renoir, Julie Manet, 1887

- ORNANS

- Claude Monet, Tempête, côtes de Belle-Île,1886

- PONT-AVEN

- Vincent van Gogh, Eugène Boch, 1888

- ROME

- Édouard Manet, Le Citron, 1880

- ROUBAIX

- Auguste Renoir, Le Garçon au chat,1868

- Camille Pissarro, La Bergère, 1881

- Edgar Degas, Petite danseuse de quatorze ans, 1931

- Edgar Degas, Giovanna Bellelli, 1856

- Edgar Degas, L’écolière, 1880

- ROUEN

- Alfred Stieglitz, Photochrome Engraving Company, Icy Night, 1903

- Clarence Hudson White, Manhattan Photogravure Company ; Alfred Stieglitz ; Experiment 27, 1909

- Heinrich Kühn, Alfred Stieglitz ; Rogers and Company, Study, 1911

- Anonyme, Salle à manger de Robert de Montesquiou, 1889, 1900

- Étienne Carjat, Whistler ‑ Peintre américain, 1865

- Paul Burty Haviland, Femmes en kimono dans Central Park, 1908

- Paul Burty Haviland, Femme en kimono à l’ombrelle dans Central Park, 1916

- Paul Burty Haviland, Florence Peterson de profil, tenant un miroir, 1910

- Paul Burty Haviland, Florence Peterson allongée, en kimono à fleurs, 1910

- Paul Burty Haviland, Florence Peterson, 1910

- John White Alexander, Portrait gris, 1893

- Charles Cottet, Lucien Simon, 1907

- Sir William Rothenstein, Charles Conder, 1915

- Olga Boznanska, Jeune femme en blanc, 1912

- William Merrit Chase, L’éventail de plumes, 1916

- Fernand Khnopff, Marie Monnom, 1887

- Antonio de La Gandara, Jean Lorrain, 1898

- James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Variations en violet et vert, 1871

- Odilon Redon, Le Corbeau, 1916

- Eugène Carrière, Nelly Carrière, 1890

- Eugène Carrière, Place Clichy, la nuit, 1900

- James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Arrangement en gris et noir n°1, 1871

- Edmond Aman‑Jean, Thadée‑Caroline Jacquet, 1892

- William Turner Dannat, La Dame en rouge, 1889

- Henry Lerolle, Portrait de la mère de l’artiste, 1895

- SAINT-DENIS, LA RÉUNION

- Paul Cézanne, La Table de cuisine, entre 1888 et 1890

- Paul Cézanne, Nature morte au tiroir ouvert, entre 1877 et 1879

- SAINT-LÔ

- Edgar Degas, Portrait du graveur Desboutin et du graveur Lepic

- STRASBOURG

- Alfred Sisley, Paysage, rivière, 1884, MNR

- Charles Laval, Paysage, entre 1889 et 1890

- Félix Vallotton, Maison et roseaux, 1925

- Alfred Sisley, Les Bords du Loing, entre 1878 et 1879

- TOURCOING

- Georges Seurat, Ruines à Grandcamp, MNR

- Claude Monet, Falaise de Fécamp, MNR

- Paul Gauguin, La Fenaison en Bretagne (recto) ; Bouquet de fleurs devant une fenêtre ouverte sur la mer (verso)

- Alfred Sisley, La Côte du Cœur-Volant à Marly sous la neige

- Francisco Oller, Bords de Seine

- Paul Signac, Herblay. Brouillard. Opus 208

- Auguste Renoir, Champ de bananiers

- Claude Monet, Argenteuil

- Charles-François Daubigny, Moisson

- François-Auguste Ravier, Paysage aux environs de Crémieu

- Eugène Boudin, La Jetée de Deauville

- Camille Pissarro, La Seine et le Louvre

- Alfred Sisley, Sous la neige : cour de ferme à Marly-le-Roi

- Camille Pissarro, Coin de jardin à l’Hermitage. Pontoise

- Georges Seurat, Lisière de bois au printemps

- Claude Monet, Meules, fin de l’été

- Henri-Edmond Cross, Les Cyprès à Cagnes

- Paul Signac, Avignon. Soir (le château des Papes)

- Émile Bernard, La Moisson

- Eugène Boudin, Le Port du Havre, bassin de la Barre

- Paul Cézanne, Rochers près des grottes au-dessus du Château-Noir

- Félix Vallotton, Clair de lune

- Paul Sérusier, La Barrière

- Paul Sérusier, Les laveuses à la Laita

- Théo Van Rysselberghe, L’Entrée du port de Roscoff

- Camille Pissarro, Coteau de l’Hermitage, Pontoise

- Odilon Redon, La fuite en Égypte

- Odilon Redon, Le Chemin à Peyrelebade

- Jean-Baptiste Huet, La Lande

- Jean-Baptiste Huet, Ciel d’orage

- Jean-Baptiste Huet, Ciel rose

- Maurice Denis, Tâches de soleil sur la terrasse

- Eugène Boudin, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe

- Johan Barthold Jongkind, En Hollande, les barques près du moulin

- Claude Monet, Saule pleureur

- Georges Seurat, Allée en forêt, Barbizon

- Claude Monet, La Seine à Port-Villez

- Pierre Bonnard, Paysage à la maison violette

- Édouard Vuillard, Le Jardin des Tuileries

- Alfred Sisley, La Barque pendant l’inondation, Port-Marly

- Alfred Sisley, Temps de neige à Veneux-Nadon

- Alfred Sisley, Un coin de bois aux Sablons

- Claude Monet, Le Givre

- Frédéric Bazille, Forêt de Fontainebleau

- Camille Pissarro, Chemin sous bois, en été

- Camille Pissarro, La Seine à Port-Marly, le lavoir

- Camille Pissarro, Printemps. Pruniers en fleurs

- Camille Pissarro, Chemin montant à travers champs. Côte des Grouettes. Pontoise

- Alfred Sisley, Une rue à Louveciennes

- Alfred Sisley, Lisière de forêt au printemps

- Alfred Sisley, La Seine à Suresnes

- Claude Monet, Cour de ferme en Normandie

- Claude Monet, Effet de neige à Vétheuil

- Auguste Renoir, Pont du chemin de fer à Chatou

- Piet Mondrian, Meules de foin III

- Gustave Caillebotte, Arbre en fleurs

- Claude Monet, Sur la falaise, près Dieppe

- YVETOT

- Charles Angrand, Les Villottes, entre 1887 et 1889

- Charles Angrand, Les Villottes, entre 1887 et 1889

Curatorship

- Anne Robbins, Curator of Paintings, Musée d’Orsay;

- Sylvie Patry, General Curator of Heritage

- Curatorship for the National Gallery in Washington

- Mary Morton, Curator and head of the French paintings department at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.;

- Kimberly Jones, Curator of Nineteenth-Century French Paintings, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Introduction

In Paris, on April 15, 1874, an exhibition opened that marked the birth of one of the most famous artistic movements in the world, Impressionism. For the first time, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Cézanne and Sisley came together independently to exhibit their works: clear and luminous paintings, translating with a quick and lively touch their fleeting impressions felt in front of the motif. They thus emancipated themselves from the Salon, the major official exhibition dominating Parisian artistic life, and guardian of the academic tradition. At a time marked by political, economic and social upheavals, the Impressionists proposed an art that was in tune with modernity. Their way of painting “what they see, . . . as they see it,” as art critic Ernest Chesneau wrote, surprises and confuses.

What happened during those few weeks? In a hundred or so works from the exhibition of these independent artists, or from the official Salon, “Paris 1874. Inventing Impressionism” celebrates the 150e Anniversary of a decisive spring. The exhibition explores what went on behind the scenes and what was at stake in an event that has become legendary, and which has since been widely regarded as the kick-off of the avant-garde.

Paris between ruins and renewal

In Paris, in the spring of 1874, the memory of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the revolutionary insurrection of the Commune the following year remained very vivid. The capital has been considerably degraded by these dramatic events.

In 1871, reconstruction began. This work extended the transformations begun during the Second Empire, under the aegis of the prefect of the Seine, Baron Haussmann, such as the construction of major traffic routes, the construction of stations, the creation of green spaces, and the construction of the new Opera House. Charles Garnier’s building is part of a completely remodelled district with its wide avenues and wide boulevards.

It was in the heart of the Paris of business, luxury and entertainment, in full revival, that the first Impressionist exhibition was held.

At Nadar’s

At the end of the 1860s, artists, including Monet, Sisley, Renoir, Degas, Pissarro and Bazille, developed a new style of painting, full of atmosphere and perception, with a lively touch, in the middle of nature or in the city. They are brought together in networks of friendships, or linked by aesthetic affinities and think about joining forces to organize their own exhibition, outside the official circuits and the Salon system, from which they are often excluded. Bazille is confident: “We are sure we will succeed. You’ll see that people will talk about us.”

The war of 1870, which separated them, mobilized some of them, and mowed down Bazille, breaking their momentum. Their project for an independent exhibition did not take shape until three years later, consolidated by the obvious interest of certain collectors and dealers. These artists set up a “Société anonyme des peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc.”, and went in search of additional members.

Degas, who was “agitated and working on the business, with quite success”, found premises in the ideal location, near the new opera house: the former studio of the photographer Nadar, 35 boulevard des Capucines. “There is space and a unique location,” notes Degas: seven or eight rooms, on two levels, in full light, served by a lift. Another novelty is that the exhibition will be open at night, lit by gas, to attract a wider clientele. “If we stir up a few thousand people like this, it will be beautiful,” Pissarro hopes.

Painting the present, exhibiting by oneself

On April 15, 1874, the exhibition of the “Société anonyme” opened its doors, with some 200 works selected by their authors themselves – without the sanction of a jury or the intermediary of a dealer. They are hung by them in Nadar’s studio on walls lined with reddish-brown wool. All that remains of this exhibition are written testimonies and the booklet to get an idea of it. The first room, mentioned here, which is said to have been installed by Renoir, gives pride of place to his paintings, with dazzling snapshots of modern life, the Paris of fashion and entertainment: its boulevards, its dancers and its spectators, all motifs also observed by Monet and Degas.

“You who enter, leave behind all old prejudices!” warns the critic Prouvaire, noting a few days after the opening that some of the paintings in this unnamed exhibition – since they are “anonymous” – “give above all the ‘impression’ of things, and not their ‘reality itself'”.

April 15, 1874: An independent and eclectic exhibition

The exhibition brings together 31 artists whose main thing is that they have paid their dues. They were of very different ages and backgrounds: nearly 40 years separated the dean Adolphe-Félix Cals from the younger Léon-Paul Robert, and the social milieu of the great bourgeois Degas or Morisot was very far from that of the anarchist Pissarro and the Communards Ottin and Meyer. Nor is it an aesthetic principle that brings them together, but rather the same desire to exhibit freely and to sell.

Their works are of an astonishing variety of subjects, techniques, and styles. There are half as many paintings as works on paper, including about forty prints, as well as a dozen sculptures and a few enamels. Highly sketched landscapes, hunting or racing scenes, even a view of a brothel, rub shoulders with engravings after Holbein, synagogue interiors, a bust by Ingres and enamels after Raphael… There is an entrance fee, as well as the catalogue, and the works are quite expensive. Around 3,500 visitors will see the exhibition. The company, which was largely loss-making, was dissolved.

Only a handful of paintings by Sisley, Monet, Renoir and Cézanne found buyers. One critic scoffed at the “large amount of crusts with which one could make excellent breadcrumbs for breaded chops.”

The Salon of 1874

At the Palais de l’Industrie et des Beaux-Arts, on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées – a twenty-minute walk from the Boulevard des Capucines – the Salon opens its doors on 1er May, 1874. An unmissable showcase of the artistic production of the moment, this gigantic official exhibition is an annual event where the public flocks in droves. It is also essential for artists, because for two centuries, it has been where their success and careers have been played out.

Carefully selected by a jury under the aegis of the Department of Fine Arts, several thousand works stand side by side, including nearly 2,000 paintings hung side by side: “great machines” – huge paintings with historical, religious or mythological subjects – anecdotal genre scenes, “orientalist” paintings, numerous landscapes or polished portraits. Most of these works are a far cry from the “too freshly painted” paintings of the future Impressionists, sometimes arbitrarily rejected in the 1860s.

In 1874, even if its jury was particularly severe, the Salon was “neither worse nor better” than in previous years, according to the critic Castagnary: “What it lacks is the capital work […] which […] becomes a date in the history of art. Indeed, that year, the exhibition that would go down in history was not the Salon.

The Salon, War and Defeat

Walking through the 24 rooms of paintings in the Salon, the novelist and art critic Émile Zola lamented: “Paintings, always paintings”, “as long as from Paris to America”, then, decidedly very weary, descended to the nave of sculptures, aspiring to “smoke a cigar”.

He observes that the works that fascinate the public are “the tragic scenes of the last war” which ended in the defeat of France by Prussia. These paintings and sculptures resonate with visitors, whether they are direct representations, such as Detaille’s battle scene depicting the tragic day of Reichshoffen, 6 August 1870, or much more symbolic, such as Maignan’s painting, an episode of the Norman Conquest, evoking sacrifice and mourning.

In 1874, many artists, both official and independent, saw the war up close. The Salon, which in 1872 had excluded works on this subject, opened up to this theme, which is still very topical, unlike the Commune, which will not be represented. The future Impressionists turned away from these two subjects in favor of other aspects of their time.

Convergences

In 1874, the Salon, like the first so-called “Impressionist” exhibition – from which it apparently differed in every way, in its scale and its principles of organization – also showed works offering a certain vision of the present. This centuries-old institution is no longer the showcase of an exclusively academic art; quite radical works, such as Manet’s The Railway, find their place there. Manet, who had been invited a few weeks earlier by his colleagues to exhibit with them at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, stubbornly refused, because he did not want to withdraw from the Salon – according to him, the only real battlefield that could lead to success.

However, not all the artists who were rejected – such as Eva Gonzalès, with a painting of modern life – joined the independent exhibition. Finally, no less than twelve artists preferred to multiply their chances of being seen, and of selling, by simultaneously presenting works at the exhibition of the Société anonyme and at the Salon. Even among the future Impressionists, not all of them had definitively “returned” from the Salon and many would return four or five years later.

In addition to two important “refused” paintings, this room brings together the works of artists present at both the first Impressionist exhibition and the Salon of 1874. In 1874, the dividing line between rearguard and vanguard was still very porous.

Modern life as a motif

In 1863, the poet Charles Baudelaire used “modernity” – a word that appeared in the nineteenth centurye century – a component of beauty. Industrialization, globalization, urbanization: everything is changing rapidly. At the 1874 exhibition, some thirty paintings echoed these developments and the advent of an urban and bourgeois way of life, from the domestic sphere to the renovated streets of Paris, through the development of leisure and entertainment venues. Apart from Degas, who depicts a laundress at work, the Impressionists mainly painted the “high life”, as it was then called to designate high society.

In the Salon, too, you can see scenes from modern life, but often approached in an anecdotal or moralistic way. For the Impressionists, the present time was not only a reservoir of new subjects. It is a new way of seeing and painting a world in the grip of the acceleration of time and in perpetual motion. In this way, they bring art closer to life.

Making a splash: “impression” and avant-garde

Did Impression, Sunrise really give its name to Impressionism in 1874? This is both true and false. The title of the painting, along with other landscapes by Monet, Pissarro and Sisley, inspired the journalist Louis Leroy to use the word “impressionist” ironically. But, apart from this sarcasm, the word did not yet impose itself and the painting, which went almost unnoticed in 1874, did not become famous until the beginning of the twentieth centurye century.

With this “impression”, Monet transgressed customs. In this way, he affirms his desire to transcribe a fleeting effect of light, a subjective sensation, rather than describing a place. This intention was probably reinforced by the presence in the 1874 exhibition of pastels hung nearby and sky studies by his master, Eugène Boudin, since, contrary to the customs of the official Salon, the Impressionists exhibited drawings and paintings together.

This quest for immediacy does not mean that Impressionist paintings are painted on the motif all at once. Impression, sunrise required several sessions. However, it is a question of preserving, even when the work is reworked in the studio, the freshness of the initial sensation, of giving the impression of an impression.

The School of the Outdoors

It was under this banner that the critic Ernest Chesneau brought together some of the participants in the 1874 Société anonyme exhibition.

This way of painting quickly, on the subject, nature and the changing effects of the atmosphere, has been practiced since the end of the eighteenth century. However, the Impressionists innovated, because if they did not execute their paintings entirely outdoors, they placed at the heart of the working process of the finished work, what was for their predecessors only an exercise, a preparatory stage. The importance given to landscape by Monet, Sisley and Pissarro also reflects a more general taste. Since the mid-nineteenth century, at the Salon as well as on the art market, landscape has asserted itself as the “modern genre”, in the spirit of the times. Chintreuil and Daubigny, painters of the previous generation, present at the Salon in 1874, were already revitalizing a production of landscapes in tune with the public’s nostalgia for a countryside and nature, seen as eternal and untouched, at the very moment when they were threatened by urbanization and industrialization

1877: The Impressionists’ Exhibition

On 4 April 1877, the third exhibition of the Impressionists opened its doors, thanks to the determination and funding of Gustave Caillebotte, a recent recruit who was both a painter and a patron of the arts. It succeeded the exhibitions of 1874 and 1876. Disappointing from a commercial point of view, they nevertheless established the idea that a new movement had been born. Thus, for the first and only time, the artists exhibiting in the spring of 1877 proclaimed themselves “impressionists”. They even publish a newspaper under this title. In a vast Parisian apartment located at 6 rue Le Peletier, 245 works by 18 artists are presented, including two women, Berthe Morisot and the Marquise de Rambures, a friend of Degas.

Because of its exceptional quality and the primacy given to the celebration of modern life, the 1877 edition will perhaps remain the most impressionistic of all these exhibitions. Five other collective demonstrations followed until 1886, but none had the force of a manifesto. Resolutely resistant to any theory, profoundly individualistic, the Impressionists nevertheless continued to invent new ways of seeing and painting the world.