How do filmmakers get period clothing to look the part? Inside the textile workshop where the past comes to life

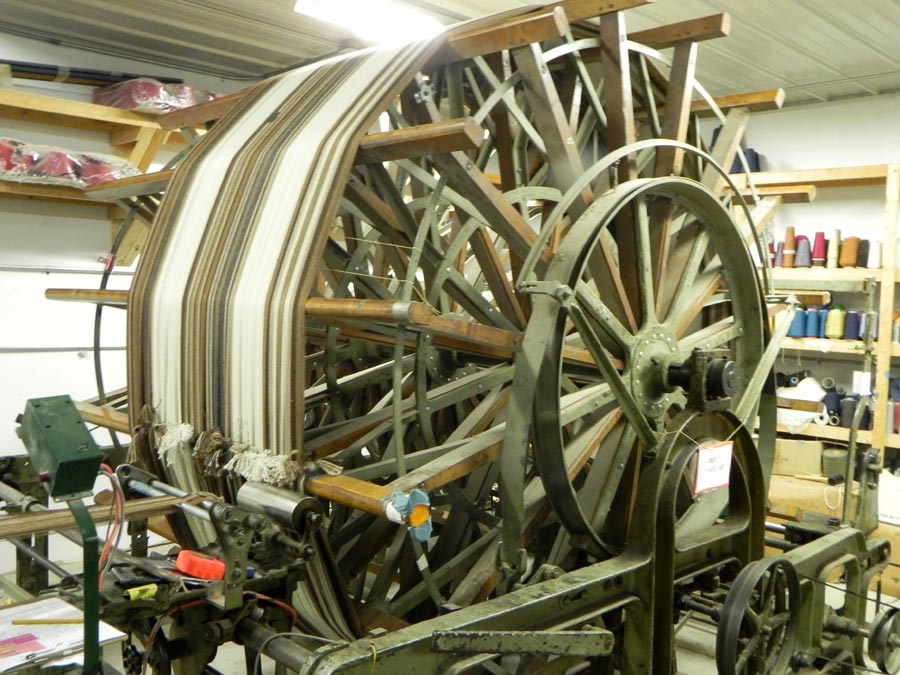

In the weave room, a worker uses a classic Crompton & Knowles loom to make suitable fabric for some 18th-century furniture. Bridget Badore

Even before you walk into the prefabricated steel building set in the woods off a country road, you’ll hear a muffled clacking sound. Once you step through the door into the workroom of Thistle Hill Weavers outside of Cherry Valley, New York, the noise from the electric-powered mechanized looms grows almost deafening. A peek into the weaving room shows workers, wisely, wearing ear protectors. Labeled archival boxes crammed on floor-to-ceiling shelves almost fill the workroom, leaving just enough space for several wooden floor looms. A large wooden worktable fills the rest of the space—where a weaver might sit and attach trim or fringe to the edge of a piece of fabric, or closely examine something right off a loom, or where, at noon, you would find the weavers eating their lunches. The mill’s owner, Susan “Rabbit” Goody—72, short and slight, in baggy trousers and a brown knit sweater, her hair in a reddish-gray braid—stands next to a weaver sitting at one of the floor looms, watching as she weaves a sample. The weaver is nervous; she knows the boss is exacting and will accept no irregularities. “Clients want our fabric because it’s incredibly custom,” Goody says.

Thistle Hill Weavers, founded by Rabbit Goody in 1989, makes textiles for movies and television shows, historic houses, and high-end furniture and clothing companies. What sets this little mill in Central New York apart from every other cloth manufacturer in the country is Goody’s remarkable ability to re-animate the past: No one else produces short runs of textiles that so faithfully replicate the weave, texture, weight and color of historic fabrics. If you’ve seen “The Gilded Age” or Cinderella Man, you’ve seen Goody’s work in action. The majority of Thistle Hill’s income comes from creating more contemporary fabrics for interior designers and architects, and from the work Goody does with historic houses, such as Mount Vernon, George Washington’s home in Virginia. Yet many of her favorite jobs have come from Hollywood costume designers seeking perfectly rendered, historically accurate textiles to recreate items like Abraham Lincoln’s shawl for the movie Lincoln or much of the colonial-era clothing seen in the 2008 mini-series “John Adams.”

Goody was born in 1951, the middle child among three girls, and raised in suburban New Jersey. When Susan was small, her father referred to her as hasenpfeffer, a term of endearment that means “rabbit stew” in German. The “rabbit” part stuck. She began weaving in her teen years because she was fascinated with the process. After graduating with a degree in cultural anthropology and ethnomusicology from Bennington College in Vermont, in 1972 she headed with friends to the rural Cherry Valley region of New York, where she made money by working as a milker on dairy farms. She bought a 150-acre former farmstead in 1975 and lived there with her first husband in a tiny cabin for five years while they built a three-story home patterned after a 1690 Connecticut house.

Goody has made money from her weaving since she was a teenager. She hand-wove cashmere-and-silk men’s scarves and sold them at large craft fairs and trade shows, and later supplied them directly to New York stores like Saks Fifth Avenue. Later, as head of the domestic arts program and curator of textiles at the Farmers’ Museum in Cooperstown, Goody became a recognized expert in early American textiles and their production. She also founded the Textile History Forum, which holds an annual conference of researchers, museum professionals and scholars.

In 1989, Goody bought an old feed mill near the village of Cherry Valley, where she set up her first mechanized power looms and hired two workers. Their first big job entailed creating denim cloth for Confederate Civil War re-enactors. Within two years, Goody had moved her growing operation to a new structure beside her house and horse farm that could hold all the machinery on one floor.

Today Thistle Hill Weavers employs seven people whom Goody has trained to run the nine mechanized shuttle looms dating from the 1890s through the 1960s, plus archaic-sounding equipment like a warp winder and a quiller—all necessary to transform big cones of thread into beautiful pieces of fabric. Goody’s workers generally arrive with no knowledge of weaving; she teaches them everything they need to know.

Over a couple of decades, Goody has traveled from Virginia to New Jersey to scavenge machinery. When she’d hear of a textile mill closing, she’d get on the phone and offer to haul the looms away until she had filled her own operation with equipment once destined for the scrap heap. She has a fondness for mechanized looms made by the legendary industrial loom-maker Crompton & Knowles from the early to mid-20th century, which she’s taught herself how to fix and keep running.

Over the past 25 years, Thistle Hill’s fabric has been sewn into clothing for films as varied as Peter Weir’s Master and Commander, the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men and Darren Aronofsky’s Noah, as well as series such as “John Adams” and “Turn: Washington’s Spies.” Occasionally, Goody even hand-weaves a piece herself, like the replica of a large fragment of the original Star-Spangled Banner, which she created for a 2019 performance by the magician David Copperfield at the Smithsonian. When a costume designer approaches Thistle Hill, Goody gathers details about the kind of fabric they want and exactly what it will be used for. Then Goody uses 21st-century technology to translate the client’s ideas into reality. She sits at a small loom attached to a computer, which she can program to create various weave patterns. She chooses threads that would work best in terms of weight, texture and color, then creates samples—small strips of woven fabric—that can be produced in a matter of minutes. Goody overnights the samples to clients. Designers love these swatches and the multiplicity of weaves to choose from. Goody’s designs are painstaking, nearly down to the microscopic level. “Just changing a yarn weight, or color, can completely change the fabric,” says Patrick Wiley, a costume designer who’s worked on several projects with Goody, including the movies Winter’s Tale and The Pale Blue Eye.

Designers like Wiley know that something as simple as the weight of a fabric in a shirt or a coat can make an actor move differently, and that this difference brings an ineffable authenticity to a given period film. Take Tom Hanks’ overcoat in Road to Perdition, a 2002 film set in the 1930s. The fabric Goody produced had the look and heft of period material—but when the coat got wet it weighed a full 32 pounds, and Hanks couldn’t walk while wearing it. “We had to weave more fabric that looked exactly the same,” Goody says, “but used much lighter materials for the coat used in the rain scenes.”

As a respected historian of American textiles, Goody brings an authority to her film projects. “She is utterly brilliant in her skills of weaving and is also immensely knowledgeable in her history,” says costume designer Joanna Johnston, who worked with Goody on Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln and Robert Zemeckis’ Here, an upcoming 2024 release, in which the narration toggles wildly between the past and the future. Goody wove the shawl for Daniel Day-Lewis to wear as Lincoln based on a careful study of the original dark wool shawl now held by the Smithsonian. When the film came out in theaters, Goody took the weavers to a matinee so they could experience the thrill of seeing their work on the big screen.

Back at the mill, when you walk into the room when the mechanized looms are running, you’ll yearn for the ear protectors the weavers wear. On one loom are yards of delicate white dimity—a lightweight cotton fabric—for the curtains in Emily’s bedroom in the Emily Dickinson house in Amherst, Massachusetts. A brightly striped Venetian carpet is taking shape on another loom. One worker is weaving fabric from spun threads of natural brown cotton—an unusual heirloom variety first grown by descendants of French settlers—for the very farmer who grew the cotton; he’ll sell it in his country store. And on the warp winder—a huge wooden wheel, a full eight feet in diameter—are multicolor and glittery threads wrapped around a beam, ready to be transferred to a loom, where a worker will weave them into fabric for a “Mandalorian” cloak. (Though much of Goody’s work is historic reproduction, some textiles are used for science fiction, and even cosplay.) Goody stops to peer closely at each piece.

Just up the road from the mill sits Goody’s house and horse farm, where she offers riding lessons and raises chickens and turkeys. She also maintains a sprawling garden, filled with greens and artichokes, tomatoes and winter squash. She grows raspberries and tends a small orchard of apple and pear trees. At 72, Goody is still out in the barn every morning at 4:15 feeding the horses.

“People ask me all the time when I’m going to retire from the mill,” Goody says, sitting in her modest office filled with shelves of reference books about textile history. “I don’t see any reason to. I love what I do.” Plus, there is no one in the wings waiting to take over. Goody is aware that she has assembled a unique set of skills that might be impossible for one single person to replicate: She’s a scholar with an encyclopedic knowledge of the materials she uses and where to find them—and she can fix hundred-year-old power looms.

For now, Goody remains at her post in the mill each day, happily quizzing clients on the phone, training weavers, inspecting fabric, creating samples and rushing orders for costume designers, all the while bringing us closer to a past that, thanks to her, feels newly tangible.

About Rabbit Goody

The odd thing was that I knew how to weave from the very beginning, as if from some past life, or like someone who can pick up a musical instrument and play without thinking about it.

I started weaving when I was in my late teens, without any real instruction – the first book I had was Sunset’s How to Weave book, but it came very naturally to me and my first real experiences were with Dee Ertel in her shop in Bennington, VT and then with Jane Keener and “Granny” at Mystic Seaport in Connecticut.

My curiosity and my interest in hand and early power technology was something that I developed throughout high school and college. The understanding of process – how things come into being – is the guiding question in all my work. My main academic interest is the transition from hand to powered technology in the textile industries.

I was a hand weaver making my living producing men’s scarves for the New York City and Boston stores during the 1970’s. I understood two very important things about hand weaving: First, no matter how good or fast I was, I could never make enough scarves to compete with machine made scarves, so I chose to weave only very exotic high-end cashmere and silk. The second thing that I recognized was that my body would not survive that type of work forever. I did fairly well in that business but my love of machinery and my understanding that the old shuttle looms could be made to produce what I wanted more efficiently led me to find mills that were going out of business and procure old commercial looms that would have been destroyed for the value of the iron.

I established the mill after working for many years at the Farmers’ Museum in Cooperstown, NY as the head of Domestic Arts and as Assistant Curator for Textiles. My husband refers to our weaving as “Heavy Metal Weaving.” We run all Crompton and Knowles equipment that dates back to the late 1890’s and as recent as the 1960’s. These looms as well as our coner, quiller and warper are all American-made industrial textile machinery. There are very few mills still running this type of loom in this country and there are no American companies still producing textile equipment.

The mill has been producing fabrics for over 26 years. We built a Morton building in 1991 and soon outgrew the space. We built an addition in 2001 and have filled that as well. I started out with just two co-workers and now we are a staff of seven.

Being able to combine several aspects of textiles is what makes my approach unique. I have spent a great deal of time studying historic textiles in museum collections because being a curator gave me access to many, many collections. I have studied weavers’ draft books and have learned to read the weavers’ recipes and receipts from the past so that I can recreate textiles that have not been seen for hundreds of years. My area of interest for historic textiles is the period between 1600 and 1870, a time when the textile industry went through changes from hand production to powered process in Europe and the United States. Woven coverlets and ingrain carpet are my most deeply researched textiles.

One of my dreams was to run a Jacquard loom and to be able to weave fabrics that were woven in the 18th and 19th centuries. Our Jacquard is a relatively small harness and can only produce limited designs for damask and ingrain carpet but it is one of the most exciting parts of our work. We have reproduced a damask pattern drawn by Marguerite Garthwaite in 1751 that may never have been woven before. The water color is in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

In addition to historic patterns, I now design very modern textiles that look as if they were hand woven but are in fact woven on our power looms. These are primarily upholstery fabrics. We are able to make our looms do things that they were never designed to do partly because they are mechanical and not electronic. We are able to fabricate parts and to change them when necessary, giving us unheard of flexibility.