Many issues arising from France’s colonial crimes in Algeria have still not been resolved

Every year, Algeria remembers the colonial crimes committed by France against the Algerian people. The North African country commemorates several such dates throughout the year: February 13 – the day of the first nuclear test, July 5 – Independence Day, November 1 – Revolution Day, which marked the beginning of the eight-year independence war of 1954-1962, and December 11 – the day on which mass demonstrations started in 1960, and were brutally suppressed by French troops.

Algeria’s colonial period lasted for over 130 years, but the nation didn’t give up on its dream of breaking free from colonial oppression. Algeria’s sovereignty was finally recognized in 1962. But independence was won with a great deal of blood. According to official Algerian data, about 1.5 million local residents died in the war with France (1954-1962), about one sixth of the country’s population at the time.

Addressing the people on the occasion of Independence Day in 2021, Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune recalled that the French colonialists were responsible for the most cruel violence, murder, and destruction in Algeria. Historians estimate that from 1830 to 1962 the colonialists caused the deaths of over five million people, including those who died as a result of contamination from nuclear tests.

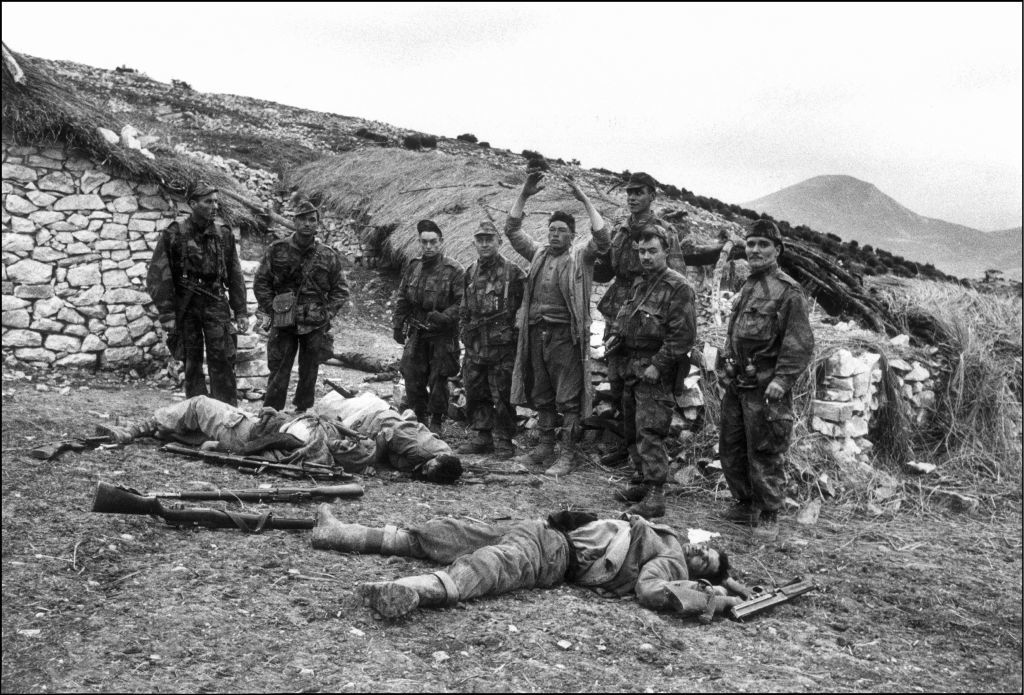

In the 1954-1962 war against the National Liberation Front (Le Front de libération nationale, FLN), the French used civilians as hostages and human shields. Historians have documented numerous cases when French colonialists exterminated entire villages. They resorted to electric shock torture, used wells as prisons, threw prisoners from helicopters, and buried people alive in mass graves which the victims were forced to dig for themselves. The European invaders used the most sophisticated and cruel methods of torture.

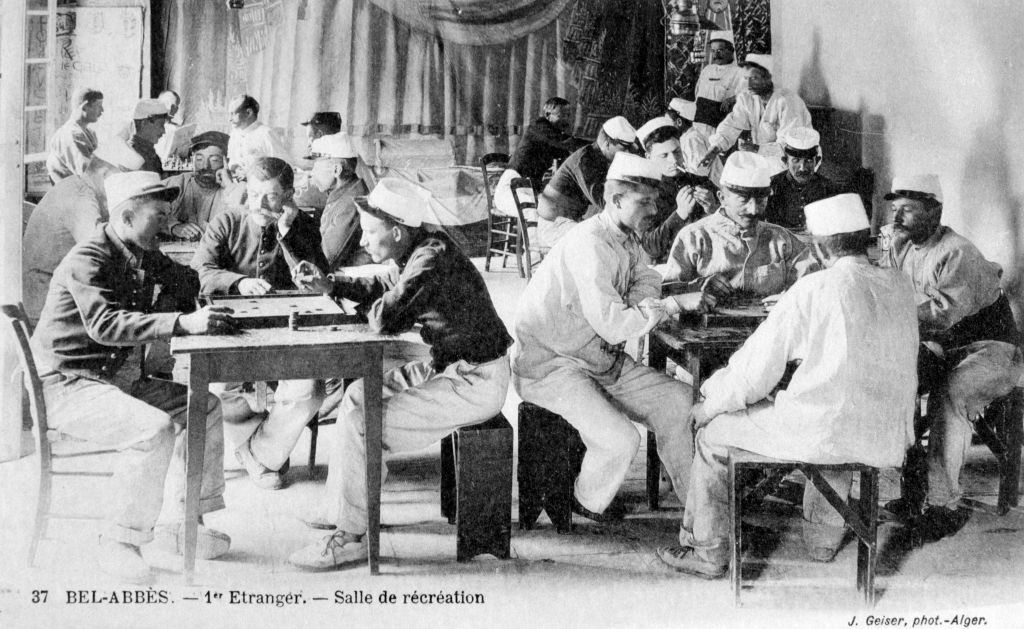

French Foreign Legion, Sidi Bel Abbes, Algeria, 20th century. French postcard. © Art Media/Print Collector/Getty Images

The Musée de l’Homme in Paris still houses 18,000 skulls acquired from dependent territories, of which only 500 have been identified, according to French media. Most of these skulls are not publicly exhibited. The skulls of several dozen Algerian resistance fighters have also been kept in the museum since the 19th century.

France’s colonial crimes affected not only people, but also Algeria’s cultural and historical heritage. During the occupation period from 1830 to 1962, the French transported hundreds of thousands of documents to Paris, including those related to the Ottoman period (1518-1830). Since gaining independence, Algeria has appealed to France to return the archive. But each time when this issue comes up, France says that according to its laws, the documents are considered classified and their disclosure is a threat to national security.

French intervention

The French invasion of Algeria in 1830 marked the beginning of the European country’s extensive colonization of Asian and African territories. The occupation process stretched on for several decades, as the local population put up an active resistance.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Algeria remained under the nominal rule of the Ottoman Empire, to which it regularly made tribute payments. However, the country retained much of its independence when it came to external political and commercial contacts. During France’s Italian and Egyptian campaigns (1793-1798) Algeria supplied Paris with wheat on credit. In the following decades, however, France refused to pay the debt, which resulted in major disagreements between the two countries.

In 1827, during one such dispute, Algeria’s Ottoman governor, Hussein Pasha, lost his temper and slapped the French ambassador Pierre Deval with a fly swatter (or a fan, according to other accounts). The King of France, Charles X, used this incident as an excuse to invade Algeria, believing that given the internal instability France was going through, an external military campaign could help rally society around the throne.

In the summer of 1830, a 37,000-strong expeditionary force from Paris arrived near Algiers and soon entered the city. Hussein Pasha capitulated. This victory did not help Charles X, who eventually abdicated, but the French remained in Algeria for the next 132 years.

Abd al-Qadir

Having occupied several Mediterranean ports, the Europeans decided to move inland, but at that point the local Arabs and Berbers, who had previously fought against the Ottoman Empire, put up strong resistance.

The anti-French movement was led by Abd al-Qadir, the son of the leader of the Qadiriyya, a local Sufi order. In November 1832, he was proclaimed as the emir of the Arab tribes in the west of the country, and united the local population in the fight against the French occupation. Abd al-Qadir was adept at managing territories and conducting guerrilla warfare, and fought against the invaders for 15 years. He became a legendary figure, and his fame spread throughout the Muslim world and Europe.

Abd al-Qadir was very popular among Algerians, since he was considered a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad (i.e. a Sharif) and a true ruler of the faithful. However, resorting to pogroms and the mass extermination of the local population, the French deprived him of the support of many military leaders and turned the course of the war in their favor.

The Algerians paid a heavy price for the resistance – hundreds of thousands died as a result of it. From 1847 to 1852, Abd al-Qadir remained in a French prison, after which he was released and went to live in exile in Damascus, where he died in 1883.

Algérie française: no rights for locals

In the following decades, Algeria was actively colonized, and the colonial territory expanded south. By 1847, there were about 110,000 European settlers in Algeria, and by 1870 this number had doubled.

In 1848, Algeria was declared a territory of France and was designated as its overseas department, with a European Governor-General in charge. The locals became subjects (but not citizens) of France. After the Ottomans were ousted from Algeria and the Abd al-Qadir movement was suppressed, the French had to deal with several other major uprisings in the 19th century, the last of which occurred in 1871-1872.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the French had conquered lands stretching from the Mediterranean Sea to the Sahara. In the 1920s, over 800,000 French settlers resided in Algeria. Three provinces – Oran, Algiers, and Constantine – became French departments. They elected representatives to the French Chamber of Deputies, but only European settlers who backed the interests of Paris could take part in these elections. Algerians did not have the right to vote.

Economic benefits

Economically speaking, the period between 1885-1930 is considered the golden age of French Algeria (and of the entire French Maghreb region). The country’s most important ports and cities were rebuilt and modernized and the agricultural sector was actively developed. Muslims had relative autonomy and retained their religious and cultural institutions.

The demographic boom, facilitated by European achievements in the fields of health and medicine, led to a threefold increase in the population, which reached nine million by the mid-20th century. Out of these, about a million were French colonists who seized about 40% of the cultivated land, which meant the most fertile land in the country belonged to them.

In other areas of life, there was also inequality between the locals and the colonizers. Local workers were paid less, and about 75% of Algerians remained illiterate. Despite these issues, however, peace lasted in the country for many decades.

Paris derived great economic benefits from its new territories. Algeria occupied a central place among France’s eastern possessions and its location was strategically important since the most convenient routes which connected France with its colonies in West and Central Africa passed through Algeria.

Fighting for independence

In May 27, 1956 file photo, French troops seal off Algiers’ notorious casbah, 400-year-old teeming Arab quarter. © AP Photo, File

The largest and bloodiest massacre committed by France in a single day occurred on May 8, 1945, when hundreds of thousands of Algerians took to the streets to celebrate the end of World War II. When people started shouting slogans demanding independence, the colonial forces opened fire on the peaceful protesters. At least 45,000 unarmed demonstrators were killed that day.

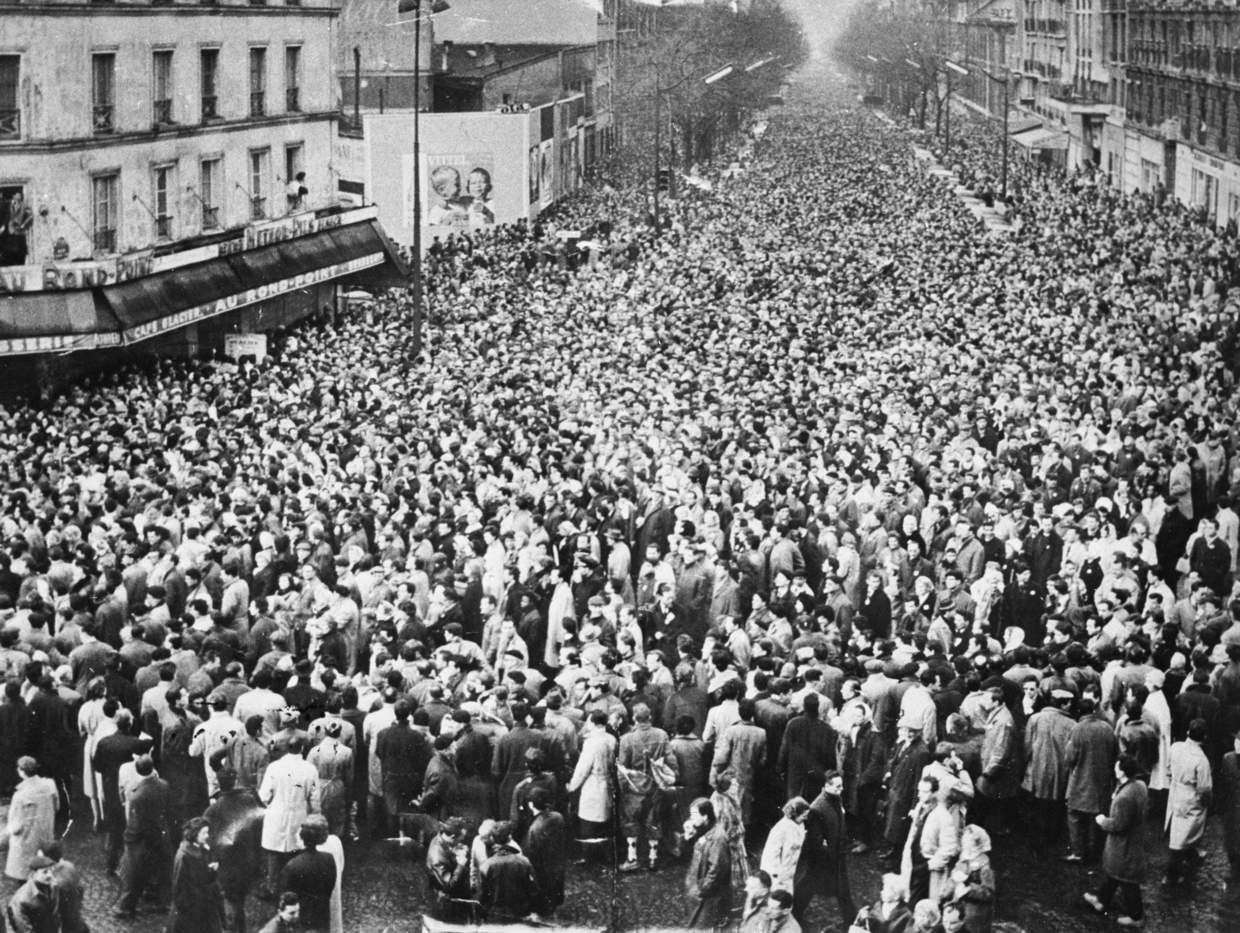

Protests broke out in France as well, and were also brutally suppressed. October 17, 1961, went down in history as the day of the “Massacre on the Seine”, or the “Paris pogrom”. On that day, about 60,000 Algerians took to the streets of Paris, demanding an end to the colonization of their country. The French authorities again used firearms against peaceful protesters, many of whom were thrown into the River Seine. The death toll amounted to 1,500, while 800 people went missing, and thousands were detained.

French soldiers looking at dead bodies during “Operation Bigeard” in March 1956, when an armed outbreak in Souk-Ahras, South of Constantine region, Algeria.

However, this did not stop the national liberation movement in Algeria. In November 1954, an alliance of several political organizations formed the National Liberation Front (le Front de Libération Nationale), which headed the armed struggle for independence. Many underground guerrilla groups also sprang up that supported the sovereignty of Algeria. At the end of 1954, they all went into attack, and this marked the beginning of the Algerian War of Independence, which lasted until March 1962.

Paris sent additional military units to Algeria to fight the rebels. An estimated 500,000 to 1.5 million local residents and over 15,000 European servicemen died as a result of the hostilities, which lasted more than seven years.

France won the war on a tactical level, but suffered a political and reputational defeat – its actions drew sharp criticism from its own citizens and the world community.

After negotiations and the signing of the Évian Accords, Algerians held a referendum and almost unanimously voted for independence, which was officially proclaimed on July 5, 1962.

he working people of Paris demanding an end to the war in Algeria. 1962.

Demining

After the war, it was necessary to clear the territory of mines. Since Algeria did not have qualified sappers, it requested assistance from European countries (Italy, Sweden, and Germany), but they refused to help. Private companies could not solve the problem either.

It was then that the USSR agreed to help Algeria, free of charge. On July 27, 1963, an agreement was signed between the Soviet leadership and Algeria. Soviet specialists removed about 1.5 million mines in Algeria from 1962 to 1965.

Nuclear tests

One of the greatest crimes against humanity was the testing of nuclear and chemical weapons of mass destruction, which was carried out by France from 1960 to 1966 in the Sahara Desert in Algeria.

A group of dummies set up on the French nuclear weapons testing range near Reggane, Algeria, before Frances third atomic bomb test, 27th December 1960.

The first nuclear explosion happened on February 13, 1960, near the town of Zaouit Reggani in southwestern Algeria and was codenamed “Gerboise Bleue”. This experiment launched the process that turned Algeria into France’s nuclear test site. The power of the nuclear bomb was estimated at 60-70 kilotons, which is about four times greater than the bomb dropped by the US on Hiroshima during WWII.

A total of 17 nuclear tests were conducted in Algeria, which led to the death of 42,000 Algerians. Many people became disabled, and the negative impact on the environment and the health of local residents is felt to this day. Algerian authorities are demanding that France hand over maps which show where the radioactive waste from these experiments was disposed of. But to this day, France hasn’t complied.

France is still there

France suffered a severe blow when it lost its largest African colony, from which it derived great economic benefit. To this day, many problems between the two countries have not been fully resolved, and echoes of imperialism are still evident in their relations.

Algeria wants France to officially admit its guilt, and take responsibility for the past events. However, in the past 60 years, Paris has never offered an official apology to Algeria, although some of its leaders made certain apologetic statements. Moreover, Algerian leaders often raise the issue of approving a bill which would criminalize the colonial policy of Paris.

After gaining independence, Algeria faced contradictory emotions – it wanted to put an end to its former dependence on France, but the well-established trade ties, the lack of experienced national government officials, and the military presence stipulated by the Evian Accords ensured the presence of France in Algeria. Moreover, Paris provided the necessary financial assistance and supplied Algeria with essential goods.

Things changed when Algerian authorities decided to nationalize industrial and energy enterprises in the late 1960s. France’s intervention in the Western Sahara conflict, in which it supported Morocco, and a stop in purchases of Algerian oil, which led to a trade imbalance in the late 1970s, further strained relations between the two countries. However, despite a decline in political relations, economic ties with France– especially those related to the energy sector – have remained strong throughout the history of independent Algeria.

Four key issues

In December 2018, Algerian Minister of War Veterans Tayeb Zitouni stated that there are four key issues (the so-called “memory file”) related to the era of imperialism: the archive of documents from the colonial and Ottoman periods, the skulls of resistance fighters which are stored in the Paris Museum, the file of people who went missing during the war of independence, and compensation for the victims of nuclear tests. Zitouni said that addressing these issues is key to ensuring normal relations between France and Algeria.

In 2020, French President Emmanuel Macron agreed to hand over the remains of 24 Algerian resistance leaders who were killed and then beheaded by French colonial troops prior to the November 1954 revolution. All of them were buried at El Alia cemetery in Algiers. Negotiations continue on the return of other skulls, the number of which is not specified.

In late 2021, new tensions sprang up between France and Algeria. In his days as a presidential candidate, Emmanuel Macron recognized the colonization of Algeria as a crime against humanity. Macron said this on February 16, 2017, during a trip to Algeria. Nevertheless, by the end of his first presidential term, the countries were on the verge of a new diplomatic crisis – Macron still had not made an official apology for the “mistakes” of the past.

Monument in Kherrata.

On October 3, 2021, Algeria decided to “immediately recall” its ambassador to France. The reaction was a response to an interview by Macron, published in Le Monde, in which he stated that since gaining independence in 1962, Algeria has lived off “income from history” which is diligently guarded by the military and political authorities, and questioned the existence of the Algerian nation prior to French colonialism. The former colony was insulted by these words.

Soon, Algerian authorities took even stricter measures. The next day, Algeria banned French military planes from its airspace. This order is still in force. In 2023, the authorities declined France’s request to open Algerian airspace for French military aircraft heading to Niger, where a military coup had taken place – an event that seriously undermined France’s influence in the region.

In an attempt to improve relations with Algeria, Macron paid a visit to the country in August 2022 and signed a new partnership agreement with President Abdelmajid Tebboune, on cooperation in various fields. However, relations between the countries remain tense. Tebboune was supposed to respond with a similar visit on May 3, 2023, but it has been postponed. The reasons are the same – Algeria is still waiting for France to take action on a number of issues, which are all related to historical memory.