Excavations of bronze age graves have found battle-scarred female archers, says the historian Bettany Hughes

In Greek legends, the Amazons were feared and formidable women warriors who lived on the edge of the known world. Hercules had to obtain the magic girdle of the Amazonian queen Hippolyte in one of his 12 labours, and Achilles killed another queen, Penthesilea, only to fall in love with her as her beautiful face emerged from her helmet.

These horseback-riding, bow-wielding nomads, who fought and hunted just like men, have long been shrouded in myth, but archaeologists are discovering increasing evidence that they really did exist.

Excavations of graves within a bronze age necropolis in Nakhchivan in Azerbaijan revealed that women had been buried with weapons such as razor-sharp arrowheads, a bronze dagger and a mace, as well as jewellery.

Archaeologists have concluded that they could have been Amazon women who lived 4,000 years ago. These fearsome women were famed for their male-free society and their prowess on the battlefield, particularly with a bow and arrow.

Historian Bettany Hughes told the Observer: “It shows that there’s truth behind the myths and legends of ancient Greece.”

Bettany Hughes at an archaeological site in Azerbaijan for her Treasures of the World series. Photograph: SandStone Global Productions Ltd

She said this evidence was all the more significant when linked to earlier finds. In 2019, the remains of four female warriors buried with arrowheads and spears were found in Russia and, in 2017, Armenian archaeologists unearthed the remains of a woman who appeared to have died from battle injuries, as an arrowhead was buried in her leg. In the early 1990s, the remains of a woman buried with a dagger were found near the Kazakhstan border.

Hughes said: “A civilisation isn’t made up of a single grave. If we’re talking about a culture that crosses the Caucasus and the Steppe, which is what all the ancients said, obviously you need other remains.”

Some of the skeletons reveal that the women had used bows and arrows extensively, Hughes observed: “Their fingers are warped because they’re using arrows so much. Changes on the finger joints wouldn’t just happen from hunting. That is some sustained, big practice. What’s very exciting is that a lot of the bone evidence is also showing clear evidence of sustained time in the saddle. Women’s pelvises are basically opened up because they’re riding horses. [Their] bones are just shaped by their lifestyle.”

She noted that the jewellery includes cornelian necklaces: “Cornelian is a semi-precious stone. You see it often when people are high priestesses or goddesses. So it’s a mark of women with status – as are mace heads.”

The finds will be revealed in a new Channel 4 series in April, titled Bettany Hughes’ Treasures of the World. One of the episodes, “Silk Roads and the Caucasus”, focuses on a part of the world that witnessed the ebb and flow of cultures and civilisations for centuries and where trade routes joined the continents of Asia and Europe.

In the documentary, she says of the Amazon finds: “Slowly you’re getting these brilliant bits of evidence that are coming out of the earth. That’s often the way, with the really best stories.”

She visits the mountain village of Khinalig in the Greater Caucasus, the highest inhabited place in Europe. It is so remote that it “feels as though it’s lost in time”, she says, noting that its local language is not spoken anywhere else.

There has been a settlement there since the bronze age, and some of its 2,000 residents tell her that, in ancient times, their women disguised themselves as men with scarves – stories handed down through their generations.

She raised ancient stories of Amazons with them: “They said, ‘all of our grandmothers fought. The men were all away with the herds. The women always used to cover their faces to fight’, which is exactly what the ancient sources said, so that people didn’t know whether they were women or men.”

Myth or fact, symbol or neurosis

None of the theories adequately explained the origins of the Amazons. If these warrior women were a figment of Greek imagination, there still remained the unanswered question of who or what had been the inspiration for such an elaborate fiction. Their very name was a puzzle that mystified the ancient Greeks. They searched for clues to its origins by analyzing the etymology of Amazones, the Greek for Amazon. The most popular explanation claimed that Amazones was a derivation of a, “without,” and mazos, “breasts”; another explanation suggested ama-zoosai, meaning “living together,” or possibly ama-zoonais, “with girdles.” The idea that Amazons cut or cauterized their right breasts in order to have better bow control offered a kind of savage plausibility that appealed to the Greeks.

The eighth-century B.C. poet Homer was the first to mention the existence of the Amazons. In the Iliad—which is set 500 years earlier, during the Bronze or Heroic Age—Homer referred to them somewhat cursorily as Amazons antianeirai, an ambiguous term that has resulted in many different translations, from “antagonistic to men” to “the equal of men.” In any case, these women were considered worthy enough opponents for Homer’s male characters to be able to boast of killing them—without looking like cowardly bullies.

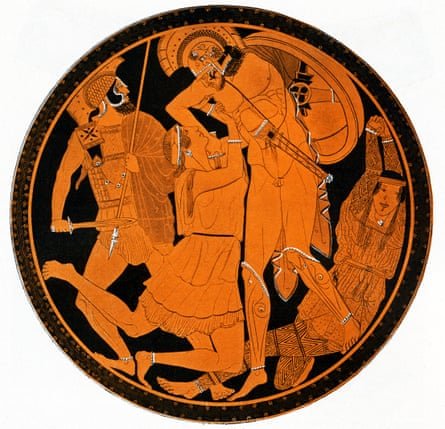

Future generations of poets went further and gave the Amazons a fighting role in the fall of Troy—on the side of the Trojans. Arktinos of Miletus added a doomed romance, describing how the Greek Achilles killed the Amazonian queen Penthesilea in hand-to-hand combat, only to fall instantly in love with her as her helmet slipped to reveal the beautiful face beneath. From then on, the Amazons played an indispensable role in the foundation legends of Athens. Hercules, for example, last of the mortals to become a god, fulfills his ninth labor by taking the magic girdle from the Amazon queen Hippolyta.

By the mid-sixth century B.C., the foundation of Athens and the defeat of the Amazons had become inextricably linked, as had the notion of democracy and the subjugation of women. The Hercules versus the Amazons myth was adapted to include Theseus, whom the Athenians venerated as the unifier of ancient Greece. In the new version, the Amazons came storming after Theseus and attacked the city in a battle known as the Attic War. It was apparently a close-run thing. According to the first century A.D. Greek historian Plutarch, the Amazons “were no trivial nor womanish enterprise for Theseus. For they would not have pitched their camp within the city, nor fought hand-to-hand battles in the neighborhood of the Pynx and the Museum, had they not mastered the surrounding country and approached the city with impunity.” As ever, though, Athenian bravery saved the day.

The first pictorial representations of Greek heroes fighting scantily clad Amazons began to appear on ceramics around the sixth century B.C. The idea quickly caught on and soon “amazonomachy,” as the motif is called (meaning Amazon battle), could be found everywhere: on jewelry, friezes, household items and, of course, pottery. It became a ubiquitous trope in Greek culture, just like vampires are today, perfectly blending the allure of sex with the frisson of danger. The one substantial difference between the depictions of Amazons in art and in poetry was the breasts. Greek artists balked at presenting anything less than physical perfection.

The more important the Amazons became to Athenian national identity, the more the Greeks searched for evidence of their vanquished foe. The fifth century B.C. historian Herodotus did his best to fill in the missing gaps. The “father of history,” as he is known, located the Amazonian capital as Themiscyra, a fortified city on the banks of the Thermodon River near the coast of the Black Sea in what is now northern Turkey. The women divided their time between pillaging expeditions as far afield as Persia and, closer to home, founding such famous towns as Smyrna, Ephesus, Sinope and Paphos. Procreation was confined to an annual event with a neighboring tribe. Baby boys were sent back to their fathers, while the girls were trained to become warriors. An encounter with the Greeks at the Battle of Thermodon ended this idyllic existence. Three shiploads of captured Amazons ran aground near Scythia, on the southern coast of the Black Sea. At first, the Amazons and the Scythians were braced to fight each other. But love indeed conquered all and the two groups eventually intermarried. Their descendants became nomads, trekking northeast into the steppes where they founded a new race of Scythians called the Sauromatians. “The women of the Sauromatae have continued from that day to the present,” wrote Herodotus, “to observe their ancient customs, frequently hunting on horseback with their husbands…in war taking the field and wearing the very same dress as the men….Their marriage law lays it down, that no girl shall wed until she has killed a man in battle.”

The trail of the Amazons nearly went cold after Herodotus. Until, that is, the early 1990s when a joint U.S.-Russian team of archaeologists made an extraordinary discovery while excavating 2,000-year-old burial mounds—known as kurgans—outside Pokrovka, a remote Russian outpost in the southern Ural Steppes near the Kazakhstan border. There, they found over 150 graves belonging to the Sauromatians and their descendants, the Sarmatians. Among the burials of “ordinary women,” the researchers uncovered evidence of women who were anything but ordinary. There were graves of warrior women who had been buried with their weapons. One young female, bowlegged from constant riding, lay with an iron dagger on her left side and a quiver containing 40 bronze-tipped arrows on her right. The skeleton of another female still had a bent arrowhead embedded in the cavity. Nor was it merely the presence of wounds and daggers that amazed the archaeologists. On average, the weapon-bearing females measured 5 feet 6 inches, making them preternaturally tall for their time.

Finally, here was evidence of the women warriors that could have inspired the Amazon myths. In recent years, a combination of new archaeological finds and a reappraisal of older discoveries has confirmed that Pokrovka was no anomaly. Though clearly not a matriarchal society, the ancient nomadic peoples of the steppes lived within a social order that was far more flexible and fluid than the polis of their Athenian contemporaries.

To the Greeks, the Scythian women must have seemed like incredible aberrations, ghastly even. To us, their graves provide an insight into the lives of the world beyond the Adriatic. Strong, resourceful and brave, these warrior women offer another reason for girls “to want to be girls” without the need of a mythical Wonder Woman